The History of Wagashi

The roots of Wagashi can be found over two-thousand years ago, when nuts were ground into a powdery state and then rolled after removal of impurities (a food that later became dango) and when mochi, said to be Japan’s oldest processed food, was made.

Wagashi evolved with the passage of time, becoming shaped by interaction with China, the development of Japanese tea ceremony, and the arrival of Western confections. Later, during the Edo period (1603-1868), the quality of Wagashi rose markedly, as the ingredients used became more available and production technologies improved. However, above all else, it is thought that the end of conflict and arrival of peace during this time were what contributed most to Wagashi’s improvement.

The Edo period was also marked by a national isolation policy that was enforced in all but a few areas of the country. Thus, it was a time when all aspects of Japan’s unique culture were enriched. Wagashi became refined in terms of their delicious taste, of course, but also their makers’ craftsmanship. Consequently, Wagashi that were very similar to those seen today came into being.

Exchanges between Japan and the outside world flourished with the arrival of the Meiji period (beginning in 1869). As modern ovens and other devices entered Japan, new Wagashi were born with the invention of more and more types, including some that were baked. What resulted are the Wagashi that we enjoy today.

Types of Wagashi

There is no standard definition of Wagashi, and consequently there are many kinds that appear similar but actually differ slightly from one another.

For example, among the confections known as Manju, there are some that are made by steaming during the production process and some that are baked in an oven.

Manju refers to the outer skin that is wrapped around bean paste. The bean paste it encloses comes in many types, including koshian, tsubuan, and tsubushian made with adzuki beans; uguisuan made with green peas; pastes made with sweet chestnuts; pastes made by mixing in sesame, yuzu, or green tea; and pastes made by adding miso.

The outer skin also comes in various types. They include skin made with wheat flour, skin made with rice flour, and skin made by mixing in brown sugar or miso. Some types are even made with Japanese sake.

The same is true of Yokan. One can find various types, including Yokan made primarily with adzuki bean-based koshian or tsubuan; Yokan from paste made with white kidney beans; Yokan made by mixing green tea, sesame, or kombu into the paste; and Yokan made with chestnut paste and dried persimmon.

From the examples provided above, it is easy to see how truly diverse Wagashi are. However, for the sake of reference, Wagashi can be generally classified as follows.

・Mochimono (confection made with rice mochi): Kashiwamochi, Daifuku, Ohagi, etc.

・Mushimono (confection made by steaming): Mushimanju, Kurimushiyokan, etc.

・Yakimono (confection made by baking; includes types that are cooked on a copper plate called a hiranabe and types baked in an oven) Hiranabemono: Dorayaki, Sakuramochi, etc. Obunmono: Kurimanju, Castella, etc.

・Nagashimono (confection made by pouring ingredients into a mold): Yokan, etc.

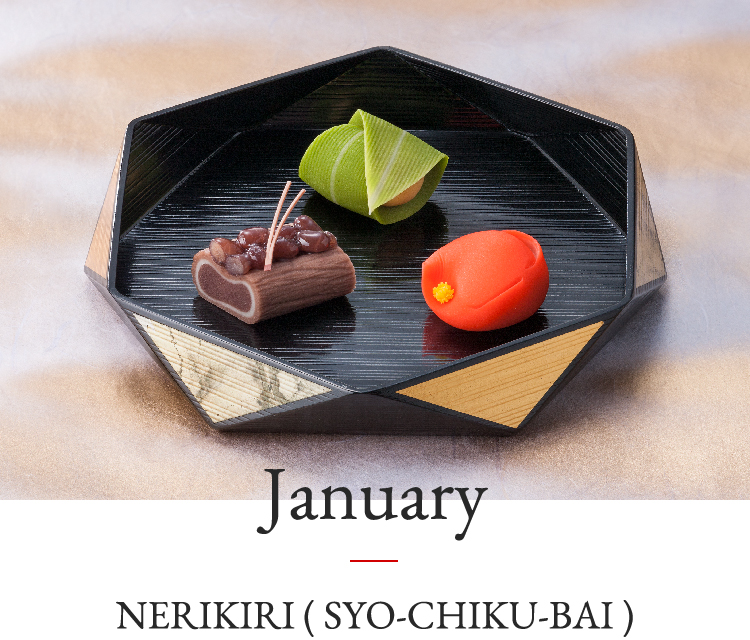

・Nerimono (confection made by shaping bean paste): Nerikiri, Konashi, etc.

・Okamono (confection made by combining separate ingredients): Monaka, etc.

・Uchimono (confection that is placed in a mold and hardened through beating): Rakugan, etc.

There are also Wagashi made by using regional characteristics or unique ingredients, as well as those made with various shapes and tastes invented by the maker.

Wagashi Characteristics

Wagashi have been nurtured and developed within Japanese life and culture for over a millennium,

and thus Japanese life is strongly reflected in them.

Wagashi have seasonal

characteristics

Japan is a country with four distinct seasons, and therefore a sense of the seasons is deeply rooted in the daily lives of its people.

Accordingly, in many cases, the Wagashi that are made change along with the seasons.

Examples include:

Hanabiramochi in January

Uguisumochi and Kusamochi in February

Kusamochi and Sakuramochi in March

Hanamidango and Itadaki in April

Kashiwamochi and Chimaki in May

Wakaayu (Yakiayu) in June

Kuzuzakura and Mizuyokan in July

August to December: Omitted

A sense of the passing seasons can be appreciated by the seasonal changes in the Wagashi offered in shops.

Generally speaking, the Wagashi mentioned in the list become unavailable for purchase when their season ends. (For example, when May ends, Kashiwamochi disappear from shops and do not appear until the following May.)

There are also Wagashi such as Nerikiri and Konashi that give a sense of the time of year by representing seasonal customs and sights with bean paste.

For example,

In January, they take the shapes of pine trees, bamboo, Japanese apricots, cranes, and turtles.

In February, they take the shapes of Japanese apricots or peach blossoms.

And in March, they take the shape of cherry blossoms.

Thus, there are Wagashi that, although made with the same bean paste, feature designs that give those who enjoy them a sense of the seasons by depicting the ever-changing natural beauties of the year.

Thus, as is clearly seen, an important characteristic of Wagashi is that they exist together with the seasonal transitions of the year.

Wagashi are a part of daily life and culture

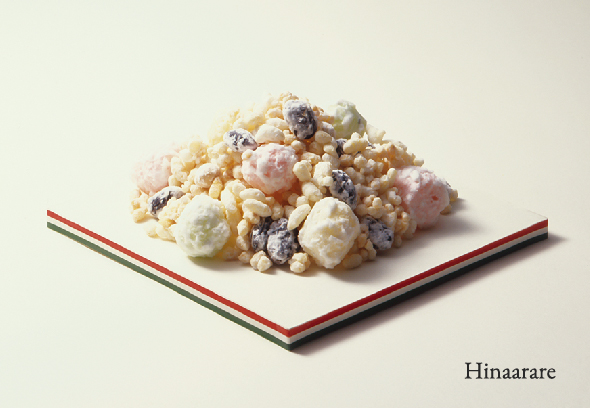

Seasonal events play an important role in the daily living and culture of the Japanese people. Each month there is some kind of event that marks the time of year. Examples include the New Year’s holiday (Oshogatsu) in January, the last day of winter in the traditional calendar (Setsubun) in February, the Dolls’ Festival (Hinamatsuri) in March, school enrollment (Nyugaku) in April, and Children’s Day (Kodomo-no-Hi) in May.

Wagashi are an essential part of those events. For example, Hishimochi and Hinaarare are enjoyed during the Dolls’ Festival in March and Kashiwamochi and Chimaki are part of Children’s Day in May. Hence, another important characteristic of Wagashi is that the types that are made change with each event.

Ingredients Used in Wagashi-Making

As there are no set rules concerning the basic ingredients that must be used in Wagashi-making, various ingredients are used. However, ingredients mainly come from vegetable sources. With the exception of chicken eggs, animal products are rarely used.

Commonly used ingredients include the beans used to make bean paste (adzuki beans, white adzuki beans, kidney beans, peas, etc.), rice (glutinous rice,non-glutinous rice,etc.), rice flour (rice ground into flour as is or after heat processing [steaming, baking, etc.]), wheat flour, sugar (caster sugar, granulated sugar, brown sugar, refined Japanese sugar, etc.), agar-agar, kudzu starch, chestnuts, tubers, persimmons, Japanese apricots, sesame, and green tea as well as chicken eggs.

Bean Pastes Used in Wagashi

Bean paste is said to be “the life of Wagashi” and is so important that it has a major effect on the taste of the finished product. Each shop’s paste has its own unique personality, as the flavor changes slightly depending on the maker.

Various types of bean paste are used in Wagashi. The following is a list of a few that are representative of them.

-

01Adzuki koshian

Paste made by boiling adzuki beans until soft, carefully removing the skins, adding water and sugar, and then kneading the mixture over heat.

-

02Adzuki tsubushian

Paste made by boiling adzuki until soft, adding water and sugar with the skins still attached, and then kneading the mixture over heat.

-

03Shiroan

Paste made by boiling kidney beans (tebo beans) until soft, removing the skins, adding water and sugar, and then kneading the mixture over heat.

-

04Uguisuan

Paste made by boiling green peas until soft, removing the skins, adding water and sugar, and then kneading the mixture over heat.

-

05Nerikirian

・Paste made by steaming Chinese yams after removing their skins, passing the softened yams through a strainer, adding shiroan, and then kneading the mixture over heat.

・ Paste made by adding water and sugar to rice flour and heating the mixture (to make gyuhi), adding shiroan, and then kneading the final mixture over heat. -

06Matchaan

Paste made by adding water, green tea, and sugar to shiroan and then kneading the mixture over heat.

-

07Gomaan

Paste made by roasting sesame and then passing the seeds through a strainer to make them smooth, adding shiroan and water, and then kneading the mixture over heat.

About

About